Supervision mechanisms in the American and European prison conditions.

Introduction

The international prohibition of torture and ill-treatment is embedded in the most important declarations and conventions of human rights[i]. The American Convention on Human Rights (ACHR hereafter) and European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR hereafter) established the absolute prohibition of torture as one of the paramount right for a democratic society[ii]. However, prison conditions are in several cases a state of exception for the inmates into this matter. Which differences and similarities could be found between America and Europe in the supervision of prison conditions and the prohibition of torture? Two judgements—one of the American Court and one of the European Court—are considered to answer this question.

The prohibition of torture is a negative obligation as is identified as a moral absolute that represents the essence of universal human rights[iii]. This prohibition is absolute for the states, for there is no margin of appreciation and it therefore represents moral absolutes not subject of consequentialist’s analysis[iv]. International law is based on the premise that individuals should not be seen as objects[v]. States have a negative obligation to refrain from engaging in any torture or ill-treatment as well as the positive obligation to prevent, investigate, prosecute and punish such acts[vi]. Thus, the breaking of the prohibition of torture cannot be justified under any circumstances. The prohibition of torture cannot be derogated, having reached the status of jus cogens[vii].

Regional Conventions: America and Europe

The ACHR enshrines the prohibition of torture under the article 5, while ECHR encloses this right under article 3; no differences in regard both articles can be found. Moreover, these articles do not include provisions for exceptions and no derogation form it is permissible for them. The ACHR embedded two organs representing the competence with respect the matters of the Convention: The American Commission (IACHR) and the American Court (IACtHR), regulated under the chapter VII and VIII respectively. However, the Council of Europe (CoE hereafter) set up the European Court (ECtHR) in the article 19 of the ECHR, establishing “the Court” as the main judicial body to protect the convention, ruling his functions and norms from the article 20 until the 51[viii].

Nonetheless, the prohibition of torture is also protected in other treaties. On the one hand, in America we find the Inter-American Convention to Prevent and Punish Torture (IACPPT) as the main treaty at regional level, created by the OAS and is controlled by the IACHR[ix]. On the other hand, in Europe, the CoE elaborated in 1987 the European Convention for the Prevention of Torture (ECPT), which embody the main instrument of supervision: the Committee for the Prevention of Torture[x].

Among the (inter)national treaties (IACPPT, ECPT and UNCAT), there can be found the same structure, providing similar functions as well as processes to complain. Nonetheless, the main difference lays in the definition of torture. Only the IACPPT’s definition is broader as does not require neither that the harm (material element) has to be serious nor a dolus especialis (subjective element) for its realization[xi]. Moreover, IACPPT’s definition refers to ‘any purpose’, and ‘methods upon a person intended to wipe out the personality of the victim or to diminish his physical or mental capacities, even if they do not cause physical pain or mental anguish’[xii].

(Inter)national instruments of supervision

In America, the IACHR and IACtHR are the instruments to supervise and protect any violation of the ACHR and the IACPPT. No other element of supervision is enshrined, whereby the American context relies on the OPCAT in order to create different instruments of social control. Conversely, in the European context, we find the European Committee to Prevent Torture (CPT)[xiii]. The CPT consists of one expert from each member state. Its modus operandi is to make announced or unannounced inspections of a sample of custodial institutions[xiv] in each member state. The real thrust of the inspection is the formal report to the relevant government[xv]. In Europe, CPT inspection standards have given vitality to judicial intervention, and court decisions have in turn reinforced CPT reports and standards[xvi]. The most recent standards document was consolidated in 2006[xvii]. However, the CPT does not include an element of supervision under domestic law by standing autonomous and flexible agencies, and this is which OPCAT address to solve.

The UN approved the Optional Protocol for the Convention Against Torture (OPCAT) in 2002 in order to provide an instrument of supervision for those countries that had previously ratified the UNCAT. The OPCAT has a dual track regulatory system: the Subcommittee for the Prevention of Torture (SPT) and the National Preventive Mechanisms (NPMs)[xviii]. The SPT is modelled upon the CPT: its membership consists of experts from States Parties and carry out visit-based inspections of places of detections in selected states, with the same modus operandi and reporting arrangements like of those of the CPT[xix]. The States Parties are interpellated to set up a NPM’s, the second regulatory strand, under their own domestic law[xx]. An important point of the NPM’s is that different agencies may be created, taking into account juridical-political complexities that may arise from multi-governance arrangements[xxi].

The applications: admissibility, merits, judgment and remedies

We have chosen two cases of torture and ill-treatment, one of the American Court (Cantoral-Benavides v. Peru[xxii]) and the other of the European Court (Peers v. Greece[xxiii]), in order to compare how the prohibition of the torture is treated in regard to the custodial or detention for suspects under state authorities. The test applied under both Courts to decide the admissibility of application is practically the same:

- Ratione personae: anyone claiming to be a victim of a violation of the IACHR or ECHR. It must not be anonymous and show that (s)he is directly affected[xxiv].

- Ratione temporis: within a period of six months from the date on which the final decision was taken[xxv].

- Ratione loci: must be under jurisdiction of the state party[xxvi].

- Ratione materiae: an applicant must allege the violation of a right that falls within the scope of the ECHR or IACHR[xxvii].

- Domestic law remedies: must be pursued and exhausted[xxviii].

- Non-duplication of procedure: the application must not be similar to another procedure already submitted to international investigation[xxix].

- Plausibility of facts: the application must be compatible with the provisions of both conventions and manifestly well-founded[xxx].

Once both cases have been found admissible, the Courts consider the merits to determine whether the rights of the applicants have been violated, i.e. if the allegations made are well founded and reveal a breach of the state party’s obligations[xxxi].

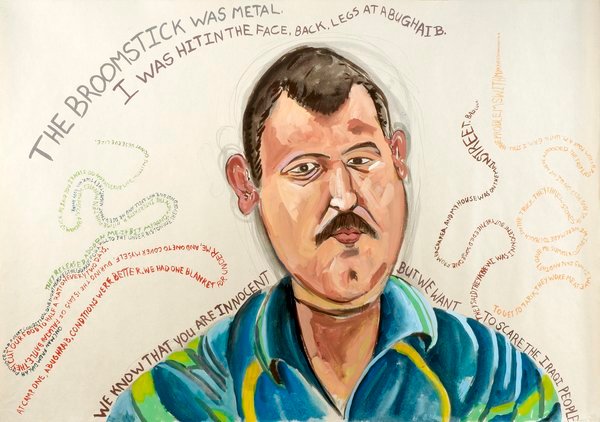

In Cantoral-Benavides v. Perú, the applicant claims a breach of the article 5 (1,2) for physical and psychological violence, incommunicado detention (para.81) and prison conditions. The latter includes strict isolation in a crowded cell, no ventilation nor light, availability of few visits and deficient medical attention (para.85). The Court stress that terrorism situation within a State cannot entail restrictions to the physical integrity of a suspect (para.96) The American Court follows the criteria applied by the ECtHR about the notion of torture and prison conditions in several statements[xxxii]. The merits also highlight the notion of psychological torture (para.102) and a double purpose against Mr. Cantoral: avoid any psychologic resistance in order to force him to waive his rights, and to subject him to additional punishment than the imprisonment[xxxiii].

In Peers v. Greece, the breach of the article 3 is focused on prison living conditions of the applicant. According to the Court and testimony, the applicant was placed in the segregation unit without his permission (para.64-69). The Court considers, in particular the applicant had to spend part of each 24-hour period confined to his bed in a cell with no ventilation nor windows, which also become sometimes unbearably hot temperatures. The applicant also had to use the toilet in presence of another inmate (para.75). The Court stress that the paramount fact remains that “the competent authorities took no steps to improve objectively unacceptable conditions of the applicant’s detention, and omission denotes lack of respect for the applicant” (para.75). The Court also relies his judgment in the CPT findings in its visits to Greece prisons (para.61). The ECtHR held that overcrowding of prisons could violate the ECPT, notwithstanding if prison authorities did not endorse or engineer the overcrowding.

Both courts declare that the State Party (Peru and Greece) violated, to the detriment of the applicants, the articles 3 (ECHR) and 5.1, 5.1 (ACHR).

The IACtHR requires the state to take all measure necessary to comply with the pending points of the reparations and costs (including payment of non-pecuniary damage to the applicant and familiars). The state must submit to the IACtHR, in a specific period of time, a detailed report on the steps taken to meet the outstanding obligations and the applicant has the right to submit comments to the State report. Moreover, the State has the obligation to continue to report the Commission every six months on the measures taken to ensure compliance with the orders given by the Court. However, the ECHR requires the State to pay the applicant in respect of non-pecuniary damage, but does not include other responsibility, as the CPT fulfil the supervision of the states and submit reports and recommendations.

Conclusion

- The IACPPT is the regional instrument that entails a broader and more explicit definition of torture; however, it has no other supervision instrument than the IACHR.

- The ECPT is paramount in Europe as an instrument of supervision to prevent torture, while the ECtHR is the judicial organ who protects any violation of the Convention.

- OPCAT entails a value-added instrument of supervision (NPMs) for those countries that do not have one.

- Prohibition of torture is an absolute right under any circumstance for both Courts, which interpretation is getting broader and does not require intent to violate it.

——-

[i] Articles 5 UDHR, 7 AND 10 ICCPR, 37 ICRC, 10 ICRMW, 15 CRPD, 3 ECHR, 5ACHR and 5 ACHPR (Bantekas and Oette, 2013:327).

[ii] Torture is considered an international crime subject to universal jurisdiction and constitutes an element of genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity. Bantekas and Oette (2013:327) make reference about the articles 6(b), 7 (1) and 8(2) of the ICC Rome Statute.

[iii] The internal structure of international human rights convention includes two types of provisions: the first impose negative obligations on states while the second lay positive duties on states. Both types of provisions are legally binding under international law, however, the normative effect produced by them is quite different. Whereas negative obligations establish a clear standard for the states regarding the ‘focal case’ of the activities prohibited by them, positive obligations do not (Candia, 2014:2; Bantekas and Oette, 2013:223).

[iv] With consequentialist’s analysis, Candia (2014), the utilitarianism moral, that is, the theory in normative ethics holding that the best moral action is the one that maximizes utility. For example, state security services cannot torture a terrorist seeking to discover where a bomb has been placed (Candia, 2014).

[v] Bantekas and Oette, 2013:330.

[vi] Bantekas and Oette, 2013:334.

[vii] Bantekas and Oette, 2013:327

[viii] The European Commission of Human Rights did the same work that the Inter-American Commission of Human Rights until the entry into force of Protocol No. 11 to the European Convention of Human Rights.

[ix] Article 16 and 17 of IACPPT.

[x] Article 1 ECPT.

[xi] Espinoza Ramos, 2012.

[xii] The IACPPT institutionalize the right to personal integrity and makes explicit reference to respect for the psychological and moral integrity of the person (para. 101, Cantoral-Benavides v. Perú). See Bantekas and Oette (2013, p.330-331) for a further detailed definition of torture.

[xiii] The CPT has been the engine-room for the development of standards for avoidance torture throughout Europe (Harding, 2012:447).

[xiv] Custodial institutions include prisons, police cells, psychiatric wards, centre for detention of immigrants, juvenile and minor centres, etc.

[xv] Harding, 2012:448.

[xvi] Harding, 2012:449

[xvii] Council for the Prevention of Torture, 2006; Harding, 2012.

[xviii] Both mechanisms are regulated under articles 2 and 17 of the convention, respectively.

[xix] However, SPT’s international scale and its limited recourses entails a very limited capacity to influence (Harding, 2012:450).

[xx] Following Harding (2012), the NPM’s are the real driver of OPCAT system. In essence, the powers and modus operandi of these NPMs will mirror the Her Majesty’s Chief Inspector of Prisons (HMCIP), which is the key agency in England and Wales in the regulation of prison conditions: independent inquiry, public annual reports, power to carry out unannounced inspections, free and unfettered access to any prison, etc (Harding, 2012: p. 441-450).

[xxi] Three main paths have been taken in the creation of NPMs: building a structure around an existing national human rights institution (NHRI), building around an ombudsman office; or creating an entirely new agency (Harding, 2012:452).

[xxii] Peers v. Greece (App.no. 28524/95).

[xxiii] Cantoral-Benavides v. Perú, 18 August 2000.

[xxiv] Art. 35.2 (a) ECHR; art. 46(d) IACHR.

[xxv] Art. 35 ECHR and art. 46 (b) IACHR.

[xxvi] Art. 34 ECHR; art. 44 IACHR.

[xxvii] Art. 3 ECHR and art. 5 IACHR.

[xxviii] Art. 35.1 ECHR; art. 46.1(a) IACHR.

[xxix] Art. 25.2(b) ECHT, art.46.1(c) IACHR.

[xxx] Art. 35.3 ECHR; art.47 IACHR.

[xxxi] However, the Courts have the option to consider admissibility and merits separately or concurrently, but it must notify the Parties if it plans to consider admissibility and merits together (Bantekas and Oette, 2013:293).

[xxxii] See paragraph 95, 97, 99, 102 of Cantoral-Benavides v. Perú.

[xxxiii] The IACtHR found that the victim was tortured to “break down his psychological resistance and force him to incriminate himself or confess to certain illegal activities” (para. 132).